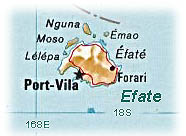

August 23, 2003Port Vila, Vanuatu Voyage to Vanuatu We arrived here in Port Vila, the capital of Vanuatu (the former New

Hebrides) yesterday morning. We hoisted the colorful red-green-gold

Vanuatu flag and the orange quarantine flag on the spreaders and anchored

in the quarantine area until the officer came to sign us in after his

lunch. Then Gunter took our dinghy, Petit Bliss, to shore and walked

to the customs and immigration offices. He completed that task before

they closed on Friday afternoon, which was a good thing. We are now

on a secure mooring in the harbor. We had rushed here, motoring with

both engines day before, wanting to complete the check-in procedures

before the week-end. We did not relish the thought of staying on Pacific

Bliss over the week-end after spending four days and nights at sea. Last night we enjoyed fellowship with yachties here at the Waterfront Cafe, then went dinner with a few of them to the Harbor View, a Chinese restaurant overlooking Port Vila’s magnificent natural harbor. We awoke this morning to a bay smooth as glass. It was delicious to get a full night’s sleep without being on watch. Today, we are headed back into the town—a short dinghy ride away. We look forward to exploring what’s there. Our passage here wasn’t anything to write home about. Of all the South Pacific passages, this 550-mile stretch from Fiji to Vanuatu is supposed to be one of the easiest—typically a run on the SE trades. We should have been making an average of 8 knots with following seas, according to the latest forecast we’d read out of Nadi, Fiji. Instead, we motored three out of the four days—averaging 6 knots—and for two days, we had a WESTERLY wind—very unusual for these parts—right on the nose. Fortunately, it was only 5-16 knots, not even close to a gale, but even so, we found it quite uncomfortable to be ensconced in the ‘washing machine’ day and night. Perhaps we are jinxed. Today, guess what? The wind ‘out there,’ we understand, has returned to the SE trades! We’ve been having the usual boat problems. During the passage, Ray, our Autopilot and third crew member, had the nerve to quit on us. The banging against the waves must have caused him to lose a connection. I hand steered for a couple of hours, on a dark, cloudy night—of course—with no moon or stars. Then Gunter found and fixed a loose cable and Ray was back on duty. The course computer, though, still has an intermittent that causes it to fail to transmit the ships GPS output to the multimeters or to the radar. (We have two back-up GPS units and the main one does work, just doesn’t output) Gunter wants to fix that problem before we sail out of here again. That means going into the “bee’s nest” of wiring underneath the Nav Station and tracing every wire. Meanwhile, we both look forward to cultural events here—especially seeing the native dancing: the men wear nothing but nambas (penis wraps made of dried pandanu or banana leaves) and the women, only grass skirts. That is actually their dress in some of the remote islands of Vanuatu. There are no bare breasts here in Port Vila. The religion is composed of 90% Christian denominations and the women wear colorful “Mother Hubbard” dresses, similar to Hawaiian muumuus but with lots of calico and lace trim. There is a charming potpourri of cultures here, a blending of Melanesian, English, French and Chinese tastes. The huge open-air market is wonderfully alive with the scent of freshly baked pastries combined with blooming frangipani. There are rows of tropical fruits, vegetables, fish, shells, artifacts and souvenir stalls. We’re waiting to try the lap-laps until some time when we arrive first thing in the morning and they’re fresh. This is Vanuatu’s national dish; it usually consists of tightly wrapped packages of dough filled with meat or fish and cooked in a ground oven. In the market, they sell them open-face style. For an overview of Vanuatu, click on the sections below: Geography of Vanuatu: ———————————————————————————————————— Geography of Vanuatu: Vanuatu is made up of some 80 different islands in the shape of a “Y” on a northwesterly slant. The northernmost islands, the Torres Group, are about 900 km from Aneityum at the southern tip. The entire land mass takes up only 12,189 square kilometers and the ocean area, 450,000 square kilometers. The islands rise high out of the sea—mountainous and volcanic—located right on the Pacific Rim of Fire, on the subduction zone of two tectonic plates. There are several permanently active volcanoes; we hope to see those on Ambrym and Tanna. The population is estimated to be around 174,000 with the majority of Melanesian origin. Two-thirds of the population live in the four main islands of Efate, Santo, Malekula and Tanna. Port Vila, the capital, is on the island of Efate. The population is increasing at a rate of 3% per year now, hence the high percentage (45%) of the population under the age of 15. Some estimates put Vanuatu’s population at about one million in the early 19th Century. But by 1870, it had decreased one-third to 650,000 and over the next 20 years it fell to 100,000. This gloomy trend continued until 1935 when the indigenous population numbered a mere 41,000. As has been the case in many other Pacific Islands we have visited, the European diseases took a terrible toll. The infection-ridden vessels of the sandalwood traders and the blackbirders brought new diseases to which the peoples of he Pacific had little resistance. Even the missionaries brought diseases, and the new converts usually succumbed first, since they were more exposed to European germs. Cholera, measles, smallpox, influenza, pneumonia, scarlet fever, mumps, chickenpox, whooping cough and dysentery—even the common cold—wiped out whole populations. Most historians agree that the ancestors of Vanuatu’s Melanesians came with a wave of migration from Southeast Asia. Australoid people began moving through Indonesia and the islands of the New Guinea chain towards Australia and the Solomon Islands. A subsequent wave finally crossed the seas from the Solomons to the Vanuatu archipelago about 3000 BC. Between the 11th and 15th centuries AD, a new wave of settlers arrived from the east. They were the sea-faring Polynesians from the central Pacific who made long-distance migratory journeys in sailing canoes holding up to 50 people. A number of Vanuatu’s oral legends tell of heroes arriving from the islands to the east, bringing new skills and customs. The first time the island group was discovered by Europeans dates back to 1606 when Pedro Fernandez de Quiros, a Portuguese mystic christened it “Terra Australia del Espirito Santo,” hence the name Espiritu Santo for the nation’s largest island. Relations were not good and Quiros left. It was not until 160 years later that Louis Antoine de Bougainville arrived and named a few more of the islands. Then in 1774, Captain James Cook discovered Vanuatu on his second Pacific Voyage on board his ship the HMS Resolution. He gave the islands their very first map and christened them The New Hebrides. But he stayed only 46 days. After that, many navigators and whalers came and went. The first settlement of Europeans dates back to 1825 when the Irishman Peter Dillon established sandalwood trade with China that—despite many clashes with the natives—survived for 40 years. As sources of sandalwood dwindled, many of the traders (mostly Australian) turned to recruiting laborers for the sugar cane fields of Fiji and Queensland, a practice known as ‘blackbirding’. A few Australian planters settled in the islands of Efate and Epi to grow coconuts for copra. Other settlers came over from Caledonia with the dream of seeing the New Hebrides annexed to France. One of them, John Higginson, purchased more than 300,000 hectors of land which he then distributed among Frenchmen and established the Compagnie Caledonienne des Nouvelles-Hebrides. Then came James Burns and Rober Philp who joined forces to acquire land in their names. This rivalry between the French and the English resulted in the establishment of the Anglo-French Condominium of the New Hebrides, created in 1906, formalized in 1914, and actually signed in 1922. So the people of Vanuatu had the British queen and the French president as joint heads of state. A lot of ‘manbush’ (simple island people) believed for a long time that they were married and that the country was ruled by this couple! During this period, indentured laborers were brought in by Asian countries to work the plantations, explaining the significant number of Vietnamese and Chinese people living here today. Americans established bases on Efate and Santo during WWII. Many of the airfields and roads they built are still being used. As the years went by, the economy slowly developed. In 1957, the South Pacific Fishing Company was established in Santo; in 1961 a manganese mine was opened at Forari, secondary schools were built, and finally tourism began to take off. The economic boom of the 1960s was the starting point of unrest for the Melanesians, who began to reclaim their land from foreigners. The Europeans viewed land as a commodity just like any other item. But this was contrary to ancient customs to the Ni-Vanuatu. They believed that land is held by present generations in trust for future generations. At this time, settlers owned about 30% of the land area—about half of that had been cleared and developed. When the planters began clearing undeveloped land for cattle ranching, protests began. Villagers argued that the settlers had no right to extend the undeveloped coastal strip any deeper into the bush that had been done already. This land, in the villagers’ opinion, was exclusively theirs. Consequently, a kastom-oriented movement called Nagriamel sprang up, operating first from Santo. By the late 1960s, spurred on by reports of the acquisition of large blocks of land by U.S. developers, Nagriamel had expanded to other islands in northern Vanuatu. In 1971, under the leadership of charismatic Jimmy Stevens, a petition was sent to the United Nations requesting independence. At the same year, the New Hebrides National Party, later called the Vanua’aku Party, was formed, consolidating support of the English-speaking Protestants (whereas Nagriamel became clearly identified with French interests.) The Francophones also supported several political groupings that were often at odds with each other. The Francophones were strongly opposed to the UK’s declared aim of early independence for the archipelago. They became known as the Moderes (Moderates) because most wanted the Condominium to remain as it was or to be replaced by French rule. They did support greater autonomy for individual islands, however. As Vanuatu became more politicized the Condominium authorities agreed to hold the country’s first general election. A newly created assembly made up of non-elected members allowed the minority parties to govern until the election in 1979 produced a clear winner. This was the Vanua’aku Party, with Lini as the chief minister. The road to democracy was not easy, however; the victors were extremely unpopular in some areas, particularly on Santo and Tanna. Nagriamel had been beating the secessionist drum since 1976 and now most of Santo’s French community joined in. The French government, seeing the Anglophones sweeping all before them and their own influence visibly declining, began supporting the Moderes. By early 1980, with threats of secession were being made on Santo and Tanna, but the English and French could not agree on how to react. The UK wanted to respond militarily, but France said ‘non’. Later in May matters came to a head. An insurrection in Tanna split the island between government supporters and rebel Moderes. On Santo, secessionists seized Luganville and hoisted the flag of the independent republic of Vemarana. In June several other northern islands seceded and merged. Then the Vanuatu government was able to secure the support of Papua New Guinea; they would send troops, if need be, to quell the rebellion. But that could only come after independence, due on July 30, 1980. Desperate to retain some semblance of control over the situation, France asked the UK to consider postponing the now imminent independence. When this proposal was vigorously rejected by the UK, the two colonial powers dispatched a small joint military force to restore order in Luganville. But the Anglo-French troops had no power of arrest and failed even to prevent looting. Once it attained power, the new Vanuatu government replaced them with soldiers from PNG, who quickly restored order and arrested the secessionist ringleaders. Following Stevens’ arrest, many documents came to light suggested that the French administration had played a double game throughout the episode. Officially they had backed the Lini government as the duly elected representatives of the people of Vanuatu; secretly they had supported the secessionists all along. The Vanuatu government’s desire since independence has been for development to benefit everyone equally, while preserving the nation’s age-old customs and traditions. According to my source, the 3rd edition of the Lonely Planet Vanuatu, the government has established diplomatic relations with over 70 countries, signed the General Agreement of Trades and Tariffs, and declared the country a nuclear-free zone. Land ownership has remained a major issue. Differences over the matter have produced factionalism within the Vanua’aku Party. Indeed, a constitutional crisis in 1988 led to the dismissal and temporary detention of Vanuatu’s first president, Ati George Sokomanu. Undoubtedly, as with our six months in Fiji, we will discover more about the current political situation as we live in the country. Certainly, so far, we are unaware of daily signs of ethnic strife of the kind we observed between the Indians and Fijians in our last port of call. Vanuatu claims the highest concentration of languages per head of population

of any country in the world! There are at least 105 local languages

as well as the more widely spoken English, French and Bislama. The national

language is Bislama, a form of pidgin English. Here are some examples:

journal107.html |

|

|