February 14-18, 2007

Uligan Island, The Maldives

Coral Mining in the Maldives

by Lois Joy

During our uneventful five-day passage from Sri Lanka, I had been dreaming of snorkeling in the pristine reefs of the Maldives. The Indian Ocean Cruising Guide, our Bible for this leg of our world circumnavigation,had urged me on: “This atoll chain has been long renowned for its diving and little else needs to be said. The diving is excellent everywhere with lots of pelagic fish including mantas and sharks. Good healthy reefs…”

During our uneventful five-day passage from Sri Lanka, I had been dreaming of snorkeling in the pristine reefs of the Maldives. The Indian Ocean Cruising Guide, our Bible for this leg of our world circumnavigation,had urged me on: “This atoll chain has been long renowned for its diving and little else needs to be said. The diving is excellent everywhere with lots of pelagic fish including mantas and sharks. Good healthy reefs…”

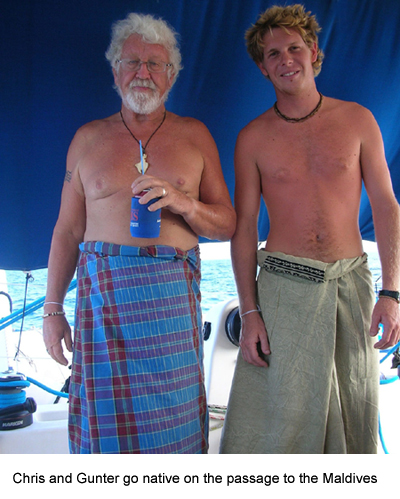

With Captain Gunter at the helm, and Chris, our crew, at the anchor locker, I drop the hook at 30 feet. It snakes all the way down into crystal cobalt waters and nestles into white coral sand. I can’t wait to jump in, right off the swim platform. But technically, we can’t leave the boat while flying our orange quarantine flag.

By 9:30 A.M., the immigration boat arrives. Four smartly dressed men in color-coordinated uniforms, one for each branch of service: customs, immigration, port control, and health, step up into the cockpit of Pacific Bliss. One man—wearing a light beige short-sleeved shirt and dark tan, creased pants with chunky, shiny black shoes—takes charge. A gentle smile creases his dark Tamil Indian face as he motions for the others to sit around the cockpit table. A younger man wearing a light green shirt with dark green pants—a colorful IMMIGRATION insignia on his sleeve—slides in. The other two—wearing blue and navy—follow. The table is covered with a multitude of documents, but the officials carefully fill out and stamp each one, then Gunter stamps each document again with the Pacific Bliss boat stamp. Stamp, stamp, stamp. How developing country bureaucrats love those stamps! I bring out cold cans of soft drinks in stubby coolers to a round of thank yous. It is the smoothest clearance procedure we’ve encountered in a long time.

The process completed, one officer hands Gunter a list of rules:

- Visitors may not have local people come onto their boat or alongside their boat unless prior permission is obtained from customs by written request.

- Shore goers must be properly dressed (long walking shorts OK for men and women, clean neat shirts, no tanks, halters or swimsuits)

- Anchor lights are mandatory between 1800 and 0600

- No shore visits between 2200 and 0600

- No SCUBA diving

- No taking alcohol ashore

- No giving of any gifts whatsoever unless customs sees the gift in advance and approves it

- No visiting any other atolls or islands without a cruising permit (which can be obtained only in Male, the capital).

We rush to complete our chores, sweating as the relentless sun continues its climb. Then we jump in to cool off. The sea has clouded with plankton and the fish we saw earlier beneath the hull as we anchored have disappeared. No worries. Having sailed night and day to get here, we need to rest. We make plans to visit those heralded, untouched reefs later in the day.

After a rewarding nap, we dinghy to Uligan’s fringing reef, don snorkels and fins and jump in. A handful of ocean fish swim by, but there are very few colorful reef fish and no neon blue and yellow darting damselfish. As for the reefs themselves, I am sorely disappointed. They are definitely bleached. “Maybe those reefs farther out will still be alive,” says Gunter, heaving his fins back into our dinghy, Petit Bliss.

“But remember the rule list?” I answered, glumly packing my fins and snorkels back into our yellow mesh dive bag. “We can’t go to other atolls. Not without sailing to Male first, and that’s two sailing days out of our way.”

“But remember the rule list?” I answered, glumly packing my fins and snorkels back into our yellow mesh dive bag. “We can’t go to other atolls. Not without sailing to Male first, and that’s two sailing days out of our way.”

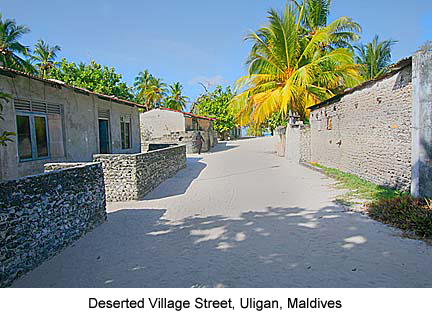

When the fiery sun begins to ease its grip on the white hot sands, we climb back into the dinghy and motor toward the island, tying Petit Bliss to the long wooden dock. At the end of the dock, we walk underneath a wooden sign, WELCOME TO ULIGAN. The first building we see on the shore is a large thatched roof structure, reminding me of the congressos (meeting huts) in the San Blas islands of Panama. The coral sand path to the village is swept hard—free of leaves and debris—making its entrance appear like a tamed tropical paradise. The atmosphere is ghostlike, yet meditative. No-one seems to be out and about. I shuffle along in my Tevas and sarong, not daring to voice my unease. There are no motor vehicles on the island; it has no airstrip; all supplies are delivered by boat, so the pedestrian-and-bicycle path we are following is the main route to the village.

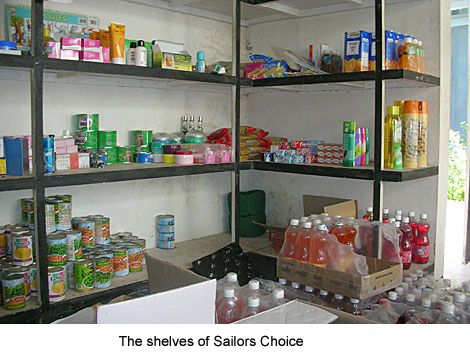

A barefooted young man dressed in a baggy white shirt over a pair of off-white, rolled up cotton pants arrives silently out of nowhere to greet us. He directs us to a provisioning store for visitors called the Sailor’s Choice, not that there are any other choices on the island! Uligan does have one other store, we discover later, for locals only. The man’s brother thrusts a provisioning notebook into my hands.

“Put yacht name at the top of new page. Then list what you want, and the day you will pick it up. Island week-end Friday and Saturday.” he says in easy-to-understand English—a welcome departure from the difficult Singhalese accented English spoken in Sri Lanka.

“Put yacht name at the top of new page. Then list what you want, and the day you will pick it up. Island week-end Friday and Saturday.” he says in easy-to-understand English—a welcome departure from the difficult Singhalese accented English spoken in Sri Lanka.

Arbitrarily, I check off what I might need; I hadn’t even thought about our provisioning onwards to Oman. We had just arrived. I am eager to see the village, and hope that an escort won’t be required. I turn toward our self-appointed guide.

“What has happened to your reef? We went snorkeling today, and there were not many reef fish; the reef is white.”

“Yes, global warming,” he slumps dejectedly.

“Yes, global warming,” he slumps dejectedly.

“Too bad, so sad,” I mumble sympathetically. He nods and straightens. End of subject. Or so I thought.

Insert or wrap Photo 06: The curved walls of coral.

Insert or wrap Photo 07: Breadfruit tree behind coral wall.

Insert or wrap Photo 08: An older style home, Uligan, Maldives

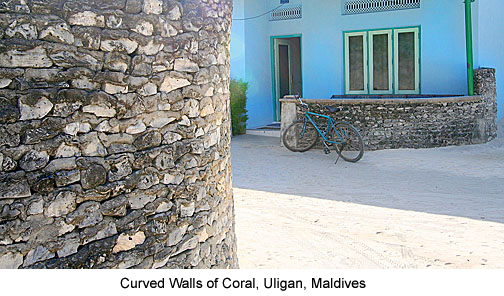

Our “guide” then directs us to the Immigration Office to pick up our papers. I marvel at the graceful, curving coral walls lining the path, peeking into meticulously maintained courtyards dominated by massive breadfruit trees, notched leaves shiny and leathery as philodendron. Although there are a few stucco houses and bamboo fences, most of the houses and courtyard walls are made of stunning blue-gray coral that shimmers in the afternoon light. Outside the walls sit cozy chairs with metal frames welded together—three or four to a row—with woven seats and backs reminiscent of ‘70s style macramé. Still, I wonder where the people are. Is it their siesta time?

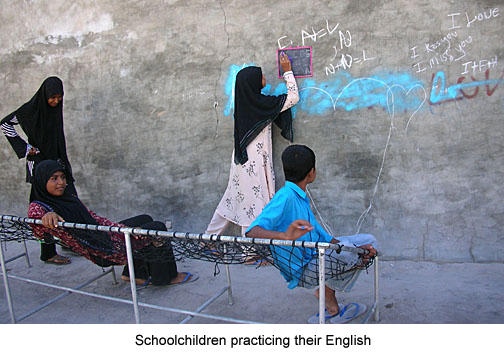

We stop to chat with a group of schoolchildren who are practicing their English. Printed on a blackboard hung on a coral courtyard wall are the words: “We love you. We miss you. We kiss you.” The three girls laugh as we joke with them; the boy is silent. One of the girls asks me whether Chris is my son. When I reply, “Just a friend helping us on our boat,” her shawl-wrapped face brightens as she turns toward Chris. “Then you can come back alone tomorrow.” Such forwardness coming from a young Muslim girl is quite a surprise.

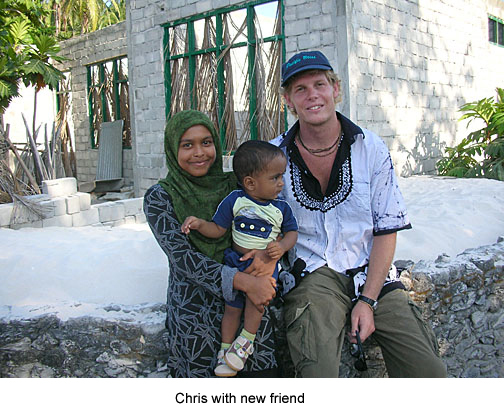

Farther down the path, we encounter another group of girls hanging out with two young mothers who appear to be only 14 or 15, already cradling babies. One of the girls begs Gunter to take a photo of her and Chris. Before he snaps it, she grabs one of babies and snuggles close to Chris. “Will you bring me back a photo of you?” she asks him.

“Tomorrow,” he promises.

“Two commitments already on your first trip ashore,” Gunter teases as we stroll along the path. “As we sail further into Muslim lands, you’d better be careful so we don’t find you followed by brothers and strung up somewhere. You’ll see less and less of their faces, until finally, there will be only slits for eyes, and if you look directly into those big black depths, you might be jailed, stoned, or worse.”

“They are the ones pursuing me,” he grins, kicking a loose coral.

As we head back to the dock, the village has begun to come alive. The women, covered head-to-toe, chat with each other in their courtyards and walk along the streets, averting their eyes as we encounter them. Men in shirts and sarongs bicycle past.

_________________

The morning sun climbs over the islands as I sip my coffee in the cockpit of Pacific Bliss. We are anchored close enough for me to watch the activity on shore. A group of women wearing Punjabi-type outfits (pants covered by flowing tunic top) and headscarves are diligently sweeping the path with fiber brooms, stooping to pick up any leaves and stray branches that have fallen from the trees. Now it all makes sense. Of course, these women would be up and outside early, beautifying their surroundings before the brutal heat of the day.

Our own morning is filled with chores as well. By afternoon, Chris connives to go ashore alone just as school lets out. Before long, he is walking along the snow white coral beach with one of the girls he has met. He delivers the photos. She presents to him a woven bracelet with MALDIVES in all caps, along with a few of her special shells.

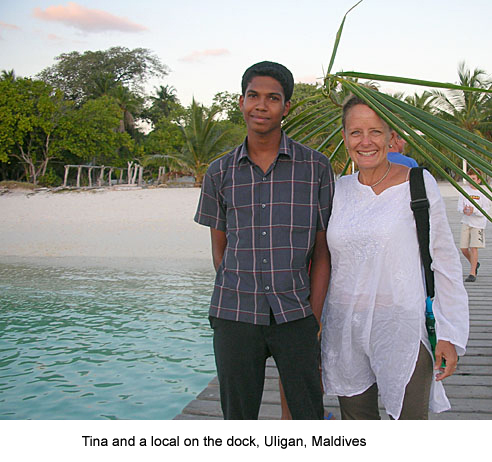

In the evening, there is a cruiser’s party on shore. Since there are no restaurants, Sailor’s Choice has organized a group of women to prepare a meal for a set fee for each guest. We sit in the courtyard in the macramé sling-back chairs with little round stools on which to set our plastic plates, setting our soft drinks on the hard-swept sand. I am introduced to the wives of the brothers who run the store, but only briefly. During the evening, I become friends with Tina, who is sailing with her husband and son on another cruising Catamaran called SCUD, anchored nearby.

Tina hails from the Bahamas and knows fishing. The talk turns to the humungous lobsters the fishermen sell to the yachties here.

"A law has been passed here against bleaching,” she says. “But I suspect that the five lobsters one fisherman is trying to sell for about $5.00 each U.S. has been bleached.” She describes this technique used by fishermen illegally in the Bahamas. The fishermen there fill a water pistol or spray bottle with liquid bleach to squirt at the lobsters. "There are no spear marks on these lobsters," she says. "And one antenna of each of them was broken off. In the Bahamas, that's how they pick them up after disabling them—by the antenna." We decide to boycott the lobsters sold here.

Our blossoming friendship helps us delve into the mysterious bleaching of Uligan’s fringing reef. The truth of the matter comes from the local English teacher who relates how the village of Uligan decided—six or seven years ago—that they no longer wanted to live in thatched huts made from coconut palms. The women yearned for beautiful homes made of cool coral bricks. So the men brought bags of powdered bleach to the reef surrounding their island and killed it. Then using crowbars and brute force, they mined the dead coral in big chunks, which they heaved into their boats. Once ashore, they cut the coral into smaller chunks, and manufactured lime cement by burning the left-over coral debris.

"At that time, we didn't know that it wouldn't come back," says the teacher. We thought that it would grow back the next year, just as trees grow new leaves,” he frowns. “We do not have a college here, to learn such things. But now we know. And now we teach such information to our schoolchildren at a very young age," he nods for our approval.

“Locals in the Bahamas also told us that global warming had destroyed some of their coral reefs,” Tina says to ease his discomfort. “But that would take generations. They did it themselves. And I suspect that this is happening in many places throughout the world.”

The next day, over sundowners with the SCUD and Pacific Bliss crews, we discuss the situation some more. “Think of the present day lives of the people who live here,” begins Gunter. “The men have to go out to remote atolls to fish, no longer paddling, but using up precious fuel.”

“But think how the lives of the women improved,” I counter. “Covered as they are, you never see them at the beach in the heat of the day. Before the sun is high and after the mid-day heat has left, then they venture out. Otherwise, they retreat into to their cool coral houses. Or they sit in their comfortable woven chairs in their protected courtyards, under the shade of their breadfruit trees, watching their children and swapping stories. A good life for them now. But ruining it for future generations.”

“Which will be ruined anyway when the rising ocean levels of global warming floods over the entire low-lying Maldives,” adds Chris. “They will be one of the first island groups to go.”

When will all those idyllic tropical islands we visited in the Pacific and Indian Oceans be flooded over? I vow to find out more when I have easy internet access.

______________________

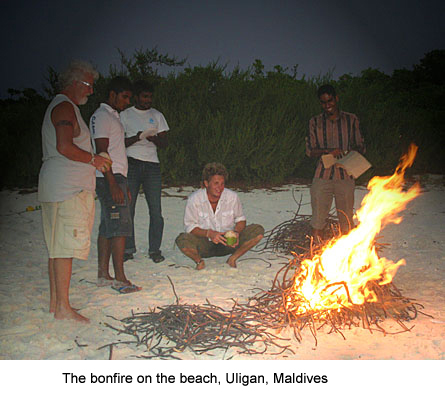

For our final night on Uligan Island, the Sailors Choice brothers plan a good-by picnic on the beach. Most cruisers have left the anchorage. The crews of SCUD and Pacific Bliss dinghy to shore. The brothers’ wives roam around the bush to collect scrap for firewood, shyly glancing our way. Then they husk young coconuts and offer them to us with a straw to sip the fresh milk. After the men stoke the bonfire until it burns to glowing embers, they place whole fishes into upright metal cages to slow cook. I serve cubes of freshly baked pumpernickel bread with honey. Tina ladles out a tasty rice casserole. As darkness falls, the event becomes an intimate gathering of two Muslim and two cruiser families. I finally have the opportunity to converse with the women. One of them had just been married for 10 months and was expecting her first child, with the usual joys and concerns that all prospective mothers have, everywhere.

Chris can be seen walking the beach, saying good-by to his new friend. A lone figure follows far behind in the shadows. Her brother is keeping an eye on them.

Links:

Go to Photogallery, Maldives

Map of Maldives

Facts on Maldives: Wikipedia

CIA Factbook: Maldives