March 2007

Aden, Yemen

The Qat Chewers of Yemen

by Lois Joy

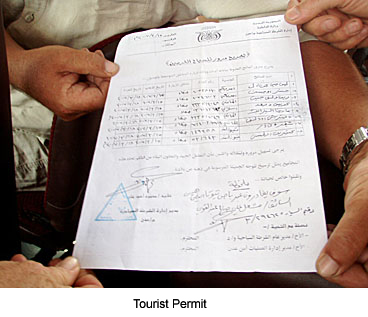

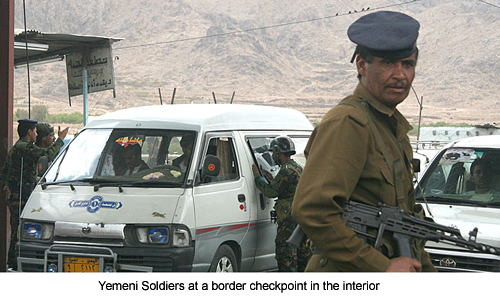

I look back at the brown-uniformed soldier with the Kalishnikov slung over his shoulder, as he stuffs a copy of our tourist permit into an unfinished box at yet another checkpoint. His right cheek bulges as if he has the mumps, or maybe it’s head-and-neck cancer.

“What is wrong with that man who took our papers?” I turn to my fellow passengers in the rickety van. “Did you see his puffed up cheek? It’s as big as a tennis ball.”

“Nein, he’s not sick,” says Renee. He and his wife Martina and their friend Dietrich of Windpocke are accompanying Gunter and me on this land tour to Sana’a, the capital of Yemen. Pacific Bliss is safely moored in the harbor of Aden. Well, relatively safe. Aden is a cruisers’ haven after sailing the gauntlet called Pirate Alley. On the other hand, it is the same harbor where 17 U.S. sailors were killed during the bombing of the U.S.S. Cole, but that was seven long years ago.

Pirate Alley. On the other hand, it is the same harbor where 17 U.S. sailors were killed during the bombing of the U.S.S. Cole, but that was seven long years ago.

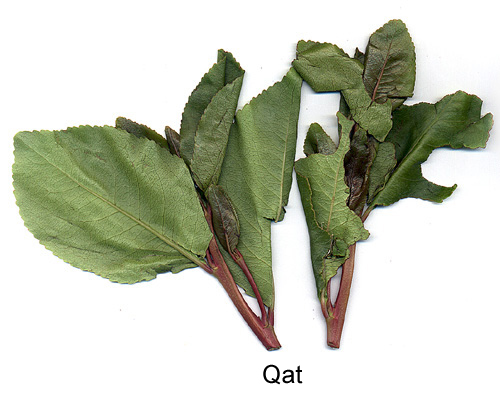

“He’s just chewing qat,” Renee continues. “They use it in a lot of countries in Africa and here on the Arabian Peninsula. They stuff the leaves of a plant into their mouths between their teeth—if they have any left—and their cheek. Then they masticate and swallow the juice. After a few hours, the mess gets smaller, more like a golf ball, and then they eventually spit it out. Makes them high, sort of like their marijuana.”

“But he is a soldier, how can he get by with it?”

“It’s legal in most of these countries around here—except for Saudi Arabia. There, possession is the death penalty. Sharia law.”

We bump along the dusty road, passing scrub and rocky hills and an occasional mud brick hovel. These people are poor, dirt poor, and I wonder how they can afford such a vice. We meet a pickup truck stacked with bundles of green plants, heading back to Aden. Two armed men ride on the back, guarding the stash.

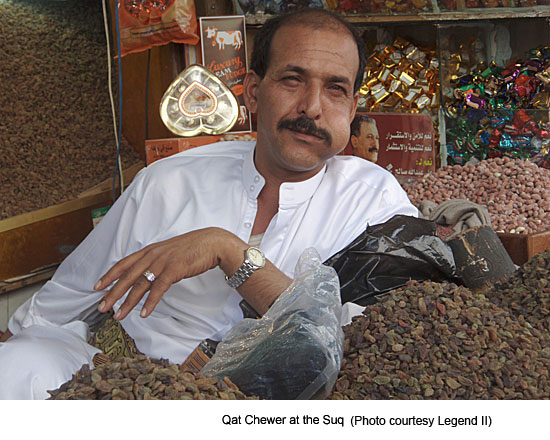

“See,” our Yemeni driver continues the conversation, “they bring qat from plantations to suq. Picked fresh this morning. Lunchtime, men go to suq to buy. Then go home.”

It turns out that most work in Yemen stops at lunch time. This is the main meal, heavy, consumed with lots of fat to fortify the digestive tract against the onslaught of the bitter leaf. After lunch, the men go to the market to search out the best product within their budget; the longest branches, with tender light green shoots, are the most prized. On average, a Yemeni can spend half his daily income on qat, so the selection process is crucial. Depending on its quality, the price of a qat rubta (bunch) needed for one “sitting” ranges from 100 to 5,000 rials (50 cents to $25.00). It is nearly impossible for the uninitiated to understand the difference between a bunch of leaves that sell for cheap and another that costs 20 times as much. The qat comes in different varieties, shapes and shades of green.

It turns out that most work in Yemen stops at lunch time. This is the main meal, heavy, consumed with lots of fat to fortify the digestive tract against the onslaught of the bitter leaf. After lunch, the men go to the market to search out the best product within their budget; the longest branches, with tender light green shoots, are the most prized. On average, a Yemeni can spend half his daily income on qat, so the selection process is crucial. Depending on its quality, the price of a qat rubta (bunch) needed for one “sitting” ranges from 100 to 5,000 rials (50 cents to $25.00). It is nearly impossible for the uninitiated to understand the difference between a bunch of leaves that sell for cheap and another that costs 20 times as much. The qat comes in different varieties, shapes and shades of green.

Once they make their purchase, there comes the inevitable discussion among friends about whose home they will go to chew the qat. Those whose homes have a big mafraj (top story room for entertaining)—or at least a large diwan (sitting room) are the most popular. Each guest is expected to bring his own qat. The host then provides the mada’a (tobacco water pipe) and drinking water, soft drinks, or tea. Chewing is very dehydrating, so these liquids are essential.

The chewers use their teeth (or a small gadget if they don’t have any left) to grind the leaves into a mulch, which is then stored in the cheek. After a couple of hours of stuffing the mouth, the mulch grows into a rather large ball from which the user extracts the juice and allows it to enter the digestive system.

At the beginning, the talk is animated and stimulating, partly due to the anticipation. (A joke making the rounds in Djibouti, Africa, is that the onlookers become high as soon as they spot the Yemeni plane in th e sky!) More and more leaves are cradled, folded and inserted into mouths. The mada’a is passed around. The atmosphere gradually becomes quiet and relaxed as the narcotic takes effect. Everyone becomes lost in their own thoughts—some call it meditating—not that it’s that easy to talk with a huge ball in one’s mouth. Toward the end of a typical session, melancholy sets in. Some users become become depressed or even psychotic. Then about sunset, it is time to head home, usually in time for the muezzin for the evening prayers.

e sky!) More and more leaves are cradled, folded and inserted into mouths. The mada’a is passed around. The atmosphere gradually becomes quiet and relaxed as the narcotic takes effect. Everyone becomes lost in their own thoughts—some call it meditating—not that it’s that easy to talk with a huge ball in one’s mouth. Toward the end of a typical session, melancholy sets in. Some users become become depressed or even psychotic. Then about sunset, it is time to head home, usually in time for the muezzin for the evening prayers.

This scenario is repeated across the country, every day, in the homes of the rich and the poor. Chewing isn’t just an addiction or a way of passing time. Here in Yemen, it is a way of life.

About 90% of Yemeni men chew qat regularly. And almost as many women. The tradition is passed along to children when they are as young as ten.

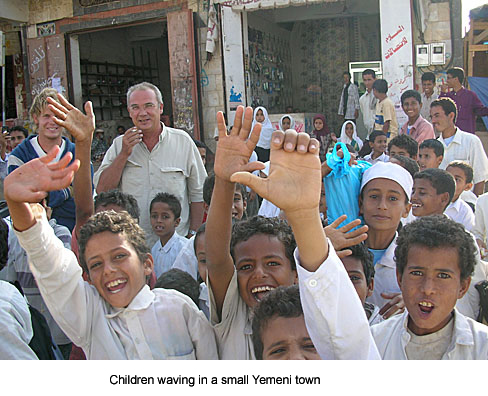

We stop for lunch at a small town. Curious children crowd around as our driver parks the van. Walking single file, our group enters the town’s only restaurant, housed in a decrepit two-story building made of unpainted wood and corrugated iron. The noon meal is chicken, floating in a greasy sauce in a dented pan atop rusty burners. We pull up stools and scoot around a dirty, unpainted wooden table. Along with the obligatory picture of President Saleh, a few torn posters of Saddam Hussein are posted onto the plasterboard  walls. The proprietor talks privately with our driver. There isn’t enough chicken for our group of nine. Just as well. Part of our group has already begun to leave after a closer look around. We all decide to buy fruit that we can peel, such as bananas, then pile back into the van. Gunter decides to treat the children gathered around, so he purchases a few bags of snacks. It is not nearly enough as more and more children suddenly appear out of nowhere. Twice, he returns to the stand to purchase more. A group of schoolgirls with white head scarves watch passively in the background as the boys shove and push into the fray. Gunter hands the girls a boxful of candy bars, and amidst cheers and smiles, we are on our way.

walls. The proprietor talks privately with our driver. There isn’t enough chicken for our group of nine. Just as well. Part of our group has already begun to leave after a closer look around. We all decide to buy fruit that we can peel, such as bananas, then pile back into the van. Gunter decides to treat the children gathered around, so he purchases a few bags of snacks. It is not nearly enough as more and more children suddenly appear out of nowhere. Twice, he returns to the stand to purchase more. A group of schoolgirls with white head scarves watch passively in the background as the boys shove and push into the fray. Gunter hands the girls a boxful of candy bars, and amidst cheers and smiles, we are on our way.

Pink plastic bags blown from the market line the hilly desert landscape for miles as we continue our way north. They catch on the dry shrubs and puff in the wind like limp balloons. “The national flower of Yemen,” I joke. But as we drive through one small town after another, the immense trash problem is no joke. The bags are joined by piles of garbage everywhere. Apparently, wherever a can or bottle is consumed, it is simply dropped.

Pink plastic bags blown from the market line the hilly desert landscape for miles as we continue our way north. They catch on the dry shrubs and puff in the wind like limp balloons. “The national flower of Yemen,” I joke. But as we drive through one small town after another, the immense trash problem is no joke. The bags are joined by piles of garbage everywhere. Apparently, wherever a can or bottle is consumed, it is simply dropped.

We stop for petrol. Our driver recommends the toilets in a building next to a petrol station. We are used to squat toilets by now, but unprepared for the wash basin. It is filthy and unusable, filled with discarded qat branches. In a large room next door, a group of men sit on rugs thrown haphazardly onto the concrete floor, lethargically chewing qat. I glance at my watch. Three o’clock. The session is winding down. As we drive through the remaining small towns along the way, we notice small groups of men sitting along the street, chewing. Some are stretched out on the sidewalks, like intoxicated winos. These are the poorest chewers, with neither a divan nor mafraj to provide a comfortable setting for their habit.

Approaching Sana’a, rocky mountains give way to a fertile valley; terraced rows of luscious green plants recede into the dusty blue horizon.

“Qat plantations,” says our driver. He points out the armed guards protecting the well-maintained fields. The mud brick houses nestled among the green are a remarkable improvement over the single story hovels we had passed along the way

“There must be a lot of money in growing qat,” I respond.

Indeed there is. Qat production has grown by more than 41% to over 147,000 tons in the decade leading up to 2006. That makes qat Yemen’s biggest cash crop, far outpacing the 22,000 tons of Yemen’s #2 crop, cotton. Qat is now Yemen’s most profitable crop, generating 25% of the gross domestic product and employing 16-25% of its workers. Despite government’s attempts to encourage the farmers to plant other crops, fruit and vegetable plots are being abandoned to grow the valuable bush. Unlike other crops, especially coffee, which requires the same environment, qat can be grown year round and fetches better prices.

Later, in Sana’a, I find two opinions about the use of qat. One sheikh who is a proponent says, “It keeps the money of the Yemeni people in Yemen, and everyone benefits—from the farmer who grows the plants, to the guards who protect the plantations, to the sellers, to the people who enjoy chewing qat. As for health concerns,” he adds, “the leaves have medicinal benefits. Qat removes stress and fatigue. It removes worms from the stomach, reduces blood pressure, and is good for diabetics.” I enquire whether it is good for women also. “Ah, Yes,” is the reply. “Our women have their own qat sessions. They believe that it is good for their health and helps reduce weight,” he chuckles. “Qat causes a loss of appetite, so they don’t have to cook much in the evening.”

Later, in Sana’a, I find two opinions about the use of qat. One sheikh who is a proponent says, “It keeps the money of the Yemeni people in Yemen, and everyone benefits—from the farmer who grows the plants, to the guards who protect the plantations, to the sellers, to the people who enjoy chewing qat. As for health concerns,” he adds, “the leaves have medicinal benefits. Qat removes stress and fatigue. It removes worms from the stomach, reduces blood pressure, and is good for diabetics.” I enquire whether it is good for women also. “Ah, Yes,” is the reply. “Our women have their own qat sessions. They believe that it is good for their health and helps reduce weight,” he chuckles. “Qat causes a loss of appetite, so they don’t have to cook much in the evening.”

But there are many drawbacks. The first is water, a scarce commodity in the Arab world. 70% of all the water in Yemen is used to grow the thirsty plant. Sana’a, the capital, is expected to run out of water by 2015. The second drawback is financial. One-third of Yemen’s agriculture is now devoted to a plant with no nutritional value. Food is imported that could be grown here, or even exported. Some Yemenis spend half their income on qat, depriving their families of the basic necessities. The third is lost productivity. In this impoverished country of 19 million, an estimated 20 million people hours per day are occupied with munching qat. Most workers close their businesses by 1:30 PM and tend to come in late the next morning because of the sleeplessness the drug induces. With qat, time loses its urgency. Past, present and future blend imperceptibly. An entire nation is dulled into a stupor.

nutritional value. Food is imported that could be grown here, or even exported. Some Yemenis spend half their income on qat, depriving their families of the basic necessities. The third is lost productivity. In this impoverished country of 19 million, an estimated 20 million people hours per day are occupied with munching qat. Most workers close their businesses by 1:30 PM and tend to come in late the next morning because of the sleeplessness the drug induces. With qat, time loses its urgency. Past, present and future blend imperceptibly. An entire nation is dulled into a stupor.

A few editorials in the Yemen Times point out qat as the cause of Yemen’s problems. Others say that qat is merely a symptom…like drug addiction in the poor inner city areas of the world. Living in one of the poorest nations outside Africa, people see chewing qat as an escape from their tough lives.

____________________________

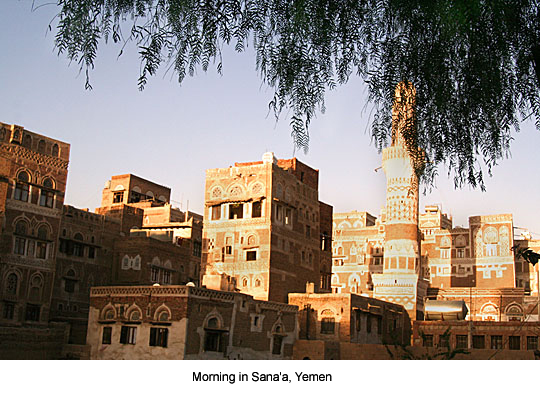

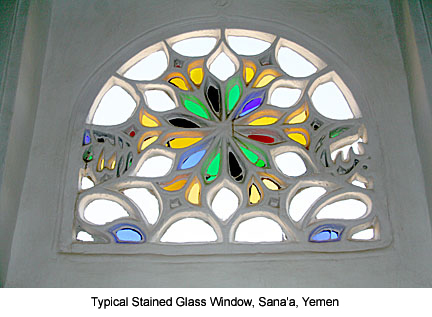

My first morning in Sana’a, I awake to the cacophony of muezzins chanting from the hundreds of minarets  gracing the Old City, a UNESCO heritage site. The sounds meld together as if in deliberate harmony. Dawn’s light spreads through the small stained glass windows of our centuries-old hotel room, a rainbow of colors dancing on the soft white plaster coating the ancient mud-brick walls. I dash in and out of the cool cement shower, apply my make-up in front of the lone mirror, and throw on a skirt (below my knees) a blouse (not too revealing) and a lightweight shawl that can double as a headscarf.

gracing the Old City, a UNESCO heritage site. The sounds meld together as if in deliberate harmony. Dawn’s light spreads through the small stained glass windows of our centuries-old hotel room, a rainbow of colors dancing on the soft white plaster coating the ancient mud-brick walls. I dash in and out of the cool cement shower, apply my make-up in front of the lone mirror, and throw on a skirt (below my knees) a blouse (not too revealing) and a lightweight shawl that can double as a headscarf.

I grope my way down the dim spiral staircase to the small reception area, nod to the proprietor, and soon I am photographing golden shafts of light weaving their way down through six-story sand-colored buildings. Called tower houses, they represent a style of architecture that dates back before the 7th century advent of Islam. The upper levels of these houses have been repeatedly rebuilt after the thinner bricks walls decayed, so most are only 200-300 years old, but the lower levels might date back to the year 1200. Everything necessary for reconstruction is found right outside the city gates: mud, clay, straw and limestone. The construction methods haven’t changed in 4000 years.

According to the Yemenis, the city of Sana’a, once called the Pearl of Arabia, is one of the first sites of human settlement. Legend has it that Noah’s son, Shem, founded the city to control the passage of caravans loaded with treasures of musk, gum, frankincense, and rare scented perfumes. As recently as 1962, the entire city nestled between the old city walls. Now the population of one million has expanded to new parts of this high plateau.

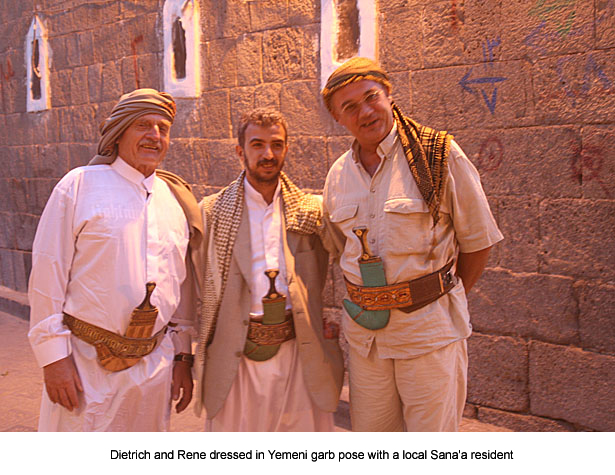

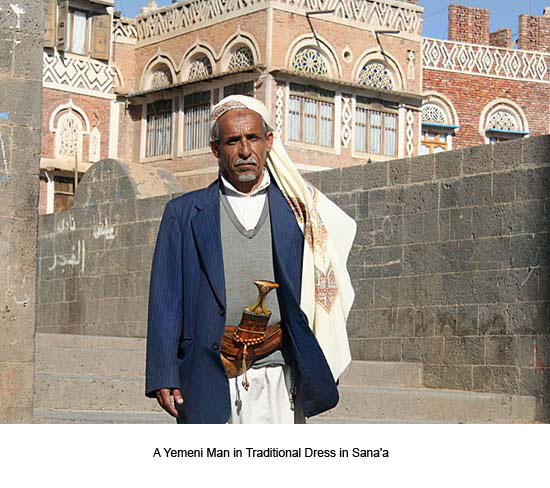

What a pleasure it is to be here—in a country that even the Lonely Planet lists as appropriate only for “dark tourism.” Awestruck, I photograph facades ornamented with intricate friezes and windows laced with delicate fretwork, filled with wonderfully colored stained glass. Everywhere, mosque minarets rise above the tower houses. The winding street takes me past hammams (bath houses) that date back to the occupation by the Ottomans in the 1800s. I nod at a trio of women clothed in black from head to toe, who furtively glance downward to avoid my eyes. Drawing a stark contrast against these ancient golden walls, the scene seems lost in time, the first setting I’ve found in which the drab Arabian abaya actually seems to fit. The Yemeni men, wearing traditional dress topped with beautifully carved belts and daggers, proudly pose for photos. By the time I return to our hotel, wide-eyed children are following me, motioning to have their photos taken.

What a pleasure it is to be here—in a country that even the Lonely Planet lists as appropriate only for “dark tourism.” Awestruck, I photograph facades ornamented with intricate friezes and windows laced with delicate fretwork, filled with wonderfully colored stained glass. Everywhere, mosque minarets rise above the tower houses. The winding street takes me past hammams (bath houses) that date back to the occupation by the Ottomans in the 1800s. I nod at a trio of women clothed in black from head to toe, who furtively glance downward to avoid my eyes. Drawing a stark contrast against these ancient golden walls, the scene seems lost in time, the first setting I’ve found in which the drab Arabian abaya actually seems to fit. The Yemeni men, wearing traditional dress topped with beautifully carved belts and daggers, proudly pose for photos. By the time I return to our hotel, wide-eyed children are following me, motioning to have their photos taken.

During breakfast in the courtyard, the discussion turns to the use of the typical six-story tall house, before many of them were turned into hotels, such as ours. The bottom floor housed animals and was used for storage; the next floor up, the diwan, was the reception area for guests; then came the floors for the kitchen and the bedrooms. The very top floor was the mafraj—the room with a view, where the man of the house held his qat parties. This room was sparsely furnished with daybeds pushed against the wall, cushions, and carpets.

“Are these parties still being held in Sana’a?” By now, I can predict the answer.

“Let’s put it this way,” answers the proprietor. “Trying to do business in Sana’a, the seat of our government, without chewing qat would be like trying to conduct business in your Washington D.C. without doing lunch, dinner, or drinks.”

I get it. There isn’t much else to do in Sana’a if you live here--no cinemas, no dancing, no pubs serving alcohol, which is forbidden by the Koran. By 2 PM, the teetotaler’s business day is shot. But if one wants to meet government officials, ministers, politicians, business owners, journalists, aid workers, poets and playwrights, one must go with the flow. Searching the net, I come across an interview with a British ex-pat who is Director for the Mercy Corps, an aid group in Sana’a: “Yemen has a dysfunctional ministry system in which officials are at work for maybe two hours a day. But if you can line up a qat chew with the official you need to talk to, you’re in.”

After a few days in Sana’a, I find that others simply chew as they go about their business day. Truck and taxi drivers chew on the road, soldiers do it on the job, despite a ban on consuming in uniform. In the suq, a city within a city, the vegetable and fruit vendors look like they are in desperate need of a dentist. And when  night falls and the suq is full of tourists and life, the haggling goes on with bulging cheeks. Children chew. And tend to run wild if their mothers are also indulging.

night falls and the suq is full of tourists and life, the haggling goes on with bulging cheeks. Children chew. And tend to run wild if their mothers are also indulging.

Taking qat away from the Yemenis would be like taking vodka away from the Russians. The tradition of chewing goes back 600 years. Legend has it that a herder found that his goats became tranquil after chewing the leaves of plants that grew in abundance on the hilly slopes of northern Yemen. They also became stronger and their milk became more nutritious. Before long, the herder decided to try the leaves himself. He shared the buzz with others who also became hooked. In time, they began cultivating the crop.

******

Back in the Aden harbor on board Pacific Bliss, Chris, our Aussie crew, is seated in the cockpit, systematically taking stalks out of a bag, one by one, pulling off their leaves, and shoving them into his mouth. He has been talked into this by a new-found Yemeni friend.

“Aren’t you going to wash them first?” I ask.

“Nah, they say washing reduces the potency,” he mumbles, trying to chew and swallow the juice at the same time.

“How does it taste?”

“Bitter. Awful.”

“Why are you doing it then?”

“Figured I should try it out while I’m here. Want some?”

“Thanks but no thanks.”

Chris chews for a few hours. Then our cruising friends dinghy over for sundowners. I set out a tray of goodies, but Chris has lost his appetite. He does take in some liquids because his mouth becomes extremely  dry. During the night, he begins to run a fever and by late morning, he is still in his berth--hot, sweating, and dehydrated--with a sore throat and a splitting sinus headache. I call my G.P. friend on another cruising yacht, Vagabond Heart, anchored nearby. She arrives promptly via dinghy and heads down into the crew hull. Chris is on antibiotics for the next week, but within a few days, he is up and around. Whether his illness was caused by chewing qat or a flu making the rounds, I’ll never know. But one thing is certain: I’ll pass on this experience!

dry. During the night, he begins to run a fever and by late morning, he is still in his berth--hot, sweating, and dehydrated--with a sore throat and a splitting sinus headache. I call my G.P. friend on another cruising yacht, Vagabond Heart, anchored nearby. She arrives promptly via dinghy and heads down into the crew hull. Chris is on antibiotics for the next week, but within a few days, he is up and around. Whether his illness was caused by chewing qat or a flu making the rounds, I’ll never know. But one thing is certain: I’ll pass on this experience!

See more photos in Photogallery, Voyage Six, Sana’a.

The Medical Effects of Qat

by Lois Joy

Qat contains cathinone, a natural amphetamine which produces a high after prolonged chewing. In the United States, it is listed as a Schedule I drug, with heroine and cocaine. However, during the maturation and decomposition of qat, cathinone is converted to cathine, which is a Schedule IV substance (legal). The conversion of cathinone can occur as early as 48 hours after the leaves are harvested. As a result, producers cut the leaves early in the morning to get them to the Yemen markets by lunchtime, when many workers leave for the afternoon for afternoon qat sessions. Some qat is exported to countries such as Somalia, Djibouti, Ethiopia and even Great Britain, but distribution must occur quickly before the qat loses its potency.

Folk medicine prescribed qat for the treatment of malaria and coughs, other doctors contend that it contains “anti-acid elements” which have a stabilizing effect on diabetes. However, there are no medically accepted benefits of qat. It can have side effects, such as constipation, hemorrhoids, hernias, paranoia and depression. In 1973, the World Health Organization listed qat as a dependence producing drug, implying that users will attempt to get daily supplies to the exclusion of all other activities. While the medical community does acknowledge the psychological dependence on qat, it is not considered a physically addictive drug.

The effects of qat include alertness, energy and euphoria. While the users report clarity of thoughts and increased concentration, medical practitioners suggest that concentration and judgment are, in fact, impaired. Qat can also result in increased aggression and “fantasies of personal supremacy.” Qat also serves as an appetite inhibitor. Reports differ regarding the use of qat as an aphrodisiac: men report increased sexual performance, though women disagree. The American Medical Association Journal reported that qat “makes most men sexually disinclined or incapable.” Long term use may produce impotence.

A study conducted at Aden University reported that more than 118 types of pesticides are used in qat cultivation. Since Yemen receives little rain, most of these chemicals are not washed off before harvesting. The Yemen Cancer Center states that qat pesticides cause approximately 70% of the cancers in Yemen. Most female qat chewers do not know that they are endangering their babies. Chewing changes the taste of breast milk as a result of the illegal pesticides used in cultivation, so most babies refuse to feed from the breast. A Yemeni organization for Women and Child Development, known as SOUL, campaigns against the dangers pregnant women pose to their unborn children by chewing qat and smoking.

Excessive qat use raises the tolerance to the chemicals in the plants, and this, in turn, raises blood pressure and the risk of heart disease. Studies conducted in Yemen showed that the incidence of heart attacks among chewers was 49% higher than in non-chewers. Regular users had bad gum disease and the tendency to lose teeth. There is a high incidence of esophageal and gastric cancers among users.

There are also issues of hygiene. Qat rooms are kept hot and dark; even in the high mafrajs, with natural air flow, the windows are closed because it is believed that the heat increases the potency of the qat. Tobacco smoke hangs in the air, qat leaves are placed on dirty carpets and chewed without washing, tea and water is drunk from cups that have not been cleansed properly, and some qat chewers have lesions in their mouths, passing on infectious diseases.

The west became increasingly suspicious of the plant after the “botched U.S.-led invasion of Somalia,” reported by The Guardian, during which many troops reportedly used top-grade qat. The military blamed the drug for some of the well-documented mistakes.

In a letter to the editor in the Yemen Times, a reader states:

“I am an American. I have recently researched the events in Somalia of October 1993. Qat is the drug that made the Somalians feel they were invincible to our U.S. Rangers and Delta Forces. The only reason our military was there was to make sure that the Somalians overcame the famine they were experiencing. Because of our military, they overcame the famine. However, this drug made the Somalians unappreciative of our efforts to help. They felt as if they could conquer the world. In reality, they only conquered in this one battle. Today, their people are still starving. I’m sorry, but we tried. Please, discontinue the use of this drug. It’s not worth it.”